From the collection of the late Mary King Chase. Courtesy Fran Pollard and Dennis Beaumont

Click on image to enlarge

Click on image to enlarge

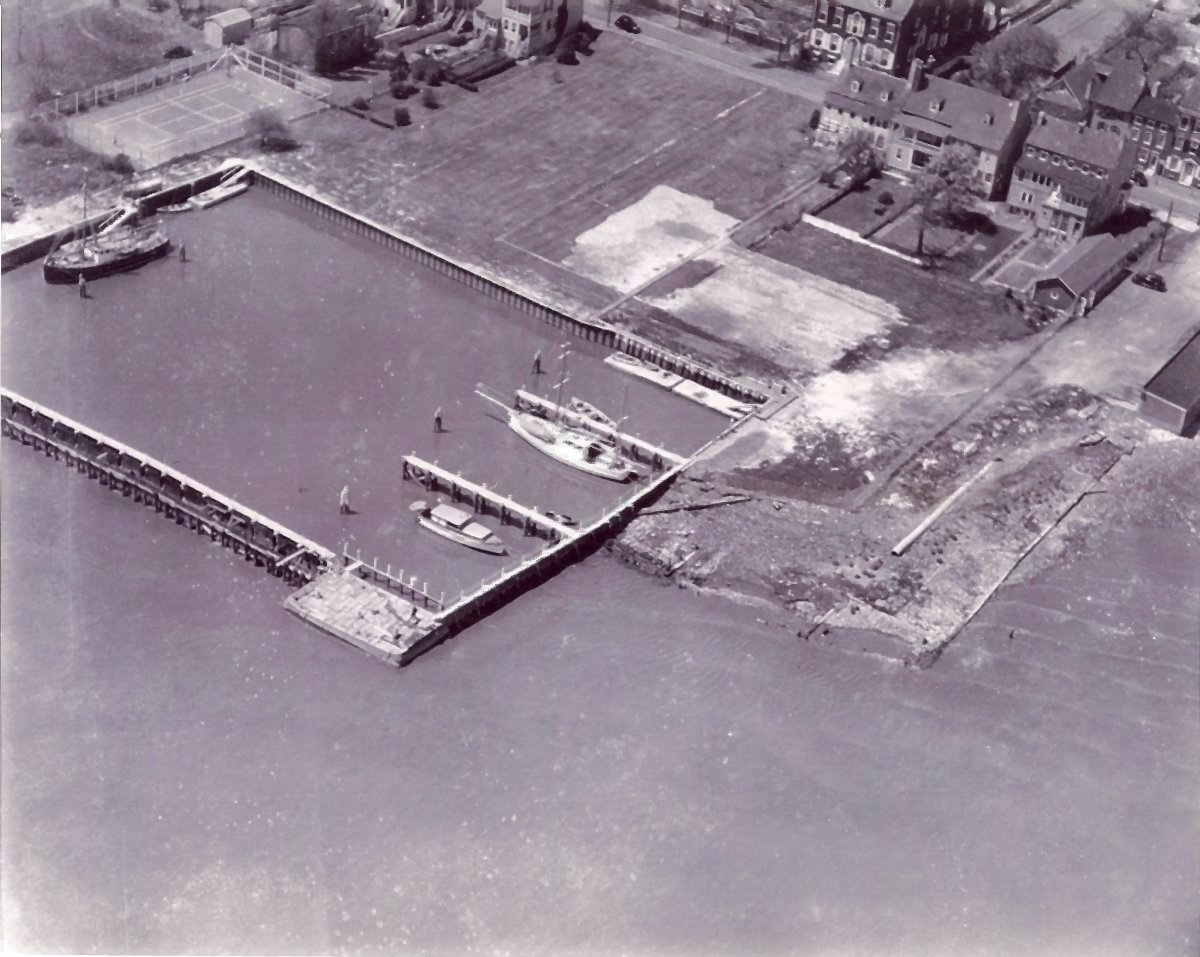

The Laird Yacht Basin

Personal recollections of Irenee du Pont, Jr.

January 15, 1986 Mr. Richard M. Appleby, Jr. President of the Trustees of New Castle Common 9 The Strand New Castle, Delaware 19720 Dear Mr. Appleby: When we talked together last September during the Philadelphia Corinthian Yacht Club Cruise, I agreed to put on paper some of my recollections of the New Castle Yacht Club. I checked my memory by examining my father's file at the Hagley Library and gleaned some additional information. Those statements in my text which came from the file at Hagley Library are identified with footnote "f". This reference is identified: Acc. 228 Irenee du Pont Series J General Office Files Nos. 115 New Castle Yacht Club 1926 - 1938 Box 131 My father was an avid golfer. This, and being president of the Du Pont Company, left little time for him to develop enthusiasm for yachting. Daddy was, however, dragged into boat ownership by mother's brothers who operated the Marine Construction Company at foot of Commerce Street in Wilmington, Delaware. One day in 1925, to his surprise, he found that he had ordered a 32 foot cruising motorboat from his brothers-in-law's firm. This boat he named Miss Take as a reflection both on how he got it and the female nature of water craft. The Miss Take proved to be more fun than Daddy expected. Her 150 h.p. English built Stirling Seagull would make her plane at speeds in excess of 20 knots. My older sisters and their young swains were quick to exploit the Miss Take for her ability to pull an aqua plane; thus engaging in a sport that preceded water skiing by decades. In 1925 the nearest thing to a marina in Wilmington was a rickety wharf at the end of D Street. A number of boats were moored bow-to-stern in the Christiana River's mid channel. Using a rowboat to get parties aboard was an awkward process. Once underway, there was a long trip at low speed between crowded river banks and through drawbridges before reaching the freedom of the Delaware River. Clearly, boat owners in Wilmington needed a better waterside facility. The man who held the key was Daddy's good friend Philip D. Laird. Phil, a founder of Laird, Bissell & Meeds, brokerage firm, had a brother married to Daddy's sister. His wife, Lydia, had an aunt married to mother's brother. The Lairds had no children. They loved antiques and parties. They lived in the George Reed House on The Strand in New Castle, Delaware. They were a fun couple. Because they were so attractive, a wide circle of friends and relatives enjoyed the hospitality at Reed House. Phil and Lydia shared another common interest with their friends and relatives. This was a healthy disrespect for the recently ratified 18th amendment to the U. S. Constitution. New Castle, being strategically located on a coastal estuary, became a natural distribution point for Canadian imports. Living so close to the Delaware River, Philip Laird simply had to have a boat, but there was no creek or other safe anchorage anywhere near New Castle. It is easy to conjecture a conversation in the Reed House taproom in which Daddy and Philip Laird conceived of a yacht basin. But when civil engineer, Albert E. S. Hall, started drawing up plans, the Reed House riparian simply was too small; More riverfront was needed. Land acquisition started in the spring of 1927. Miss Dennison sold 55 The Strand for $11,000. (f) Thus enough river frontage was secured so construction of the yacht basin could go forward. While the yacht basin was being built, another event held this seven year old boy's attention. Daddy took delivery of a sixty-two foot Elco motor yacht, which he named Icacos, reflecting a faulted spelling of the Hicacos Peninsula in Cuba where he would build a winter home. The Icacos opened entirely new perspectives in boating. The family could and did take extended cruises from Norfolk, Virginia, to Newport, Rhode Island. With the arrival of the Icacos, Walsh came into his own. Walsh had been the chauffeur since before I was born. Now, he was Cap Walsh and I was to call him Cap. Actually, he was Captain James S. Walsh, licensed Delaware River Pilot, native of Lewes, Delaware, 32nd degree mason and formerly captain of a Du Pont Company tug boat which carried workers between Wilmington and Carney's Point. Beside being master of the Icacos, he was in control of everything that happened at the New Castle Yacht Basin. Early that summer, the Chesapeake and Delaware canal was re-opened after being closed for removal of locks and excavation to sea level. I remember that Sunday when the Icacos joined a marine parade through the canal. There was a string of power yachts as far as a small boy's eye could see. Many were decorated with flags and bunting. Uncle Ernest's Alberta, a sister ship to the Icacos, ran aground at Reedy Point. Amid a lot of grown-up talk through megaphones, another yacht refloated her. Uncle Lammot, in his fifty foot Elco, signalled that he had run out of lemons. During prohibition, lemon was an essential ingredient of a concoction to which grown-ups attached a great deal of importance. Mother had supplied the Icacos with several of those grapefruit size ponderosa lemons that she lovingly had grown herself. I can still see my father handing an enormous lemon to his brother amid cheers and hee-haws. Mother explained to me that passing someone a lemon was considered a playful insult. In 1928 the opening of the New Castle Yacht Club, as Daddy called it, started a convenient new format for family boating. Mr. James Camell, who had been the boat watchman at D Street, was now ensconced in a small one- room "club house" at the corner of what looked to me like a big wooden pen full of water. The Icacos and the Alberta were tied to floating wharfs on opposite sides of the basin. The Miss Take was tied to the bulkhead at the end of the big green lawn. A sleek varnished mahogany speedboat lay just outboard of the Miss Take. I remember Daddy stopping the Cadillac touring car at the "club house". Mr. Camell, in blue bib overalls, rested his large abdomen against the door on my side where my fingers were lapping over. It was warm and soft on my knuckles. There was some grown-up talk, followed by laughter and Daddy stopped the engine. We went aboard the Icacos for a Sunday afternoon ride. Sunday afternoon cruises were necessarily short. Daddy played golf on Sunday mornings: Mother took the rest of the family to church. By the time we had lunch and got to New Castle, there was only time for about three hours on the river. This would allow a brief visit to the lighthouse keeper on Reedy Island where we could throw bread to the ducks. Perhaps, instead, we could have a swim in the deliciously oozy mud at Augustine beach. The water there was considered cleaner than at New Castle. Sometime this year Cap Walsh explained to me that the speedboat tied alongside the Miss Take was owned jointly by himself and Philip Laird. My first ride in this Cris-Craft runabout was pure excitement. Water sprayed out on each side and wind came over the windshield with hurricane force. My father's files (f) show an exchange of letters with Lt. Gen. G. B. Pillsbury of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The subject was how to stop the discharge of oil from ships in the Delaware River. "This black sticky oil covers everything on the beach, is hard to clean off of boats and is a serious fire hazard". Copies of similar letters from Ernest du Pont and Philip Laird are also preserved. This was the year that my parents gave up going to Ventnor, New Jersey, so mother's seventeen foot cat boat, White Puss, was brought up from the Jersey shore and joined the fleet at New Castle. While the Miss Take and the White Puss saw some use by my sisters and their friends, the Icacos completely overshadowed them in the eyes of a small boy. In a year or so the White Puss was sent to Rehoboth, Delaware, where the family had built a new cottage. The Miss Take was put onboard a freighter and delivered to Daddy's winter home at Varadero on the Hicacos Peninsula in Cuba. By 1931 Henry B. du Pont's fifty four foot Tequilla had joined the fleet in New Castle. There she came to an abrupt end miraculously without serious ln]ury to any person. It seems the Tequilla's galley stove burned propane gas. There was a leak one evening when the steward was on board alone. He was in the galley at the time the Tequilla was ripped by an explosion. As the story goes, the steward soared majestically through the galley skylight and landed virtually unhurt on the famous Reed House lawn. I saw the badly burned out Tequilla after she had been brought to the Marine Construction Company where she was salvaged. Her port side was completely torn from her transom and her deckhouse was gutted by fire. In 1934 the yacht basin was doubled in size to accomodate additional vessels and make it possible to manoeuvre the Icacos more safely. There seems to be no record of when the interlocking steel piling was installed to replace the old wooden bulkhead structure. My best recollection is that the iron went in with the expansion. Its cost appears to be buried in the total billings for the project. Felix du Pont's Buckeroo, a ketch rigged motor sailer, became resident at the basin about this time. My automobile driver's license in 1936 opened another new vista in yachting for me. I sold a proposition to my parents that, since I was now capable of driving a car, it was obvious that I could handle mother's seventeen foot cat boat all by myself. Acceptance of the theorem was so swift as to be almost disappointing. That my parents might view the hazards of the high seas as lesser than those of the highway did not occur to me. However, Cap Walsh had reservations. In retrospect, I see now that he had his spy on me. "Uncle Charlie" (Charles Metcalm) resident deck hand, carpenter, and painter on the Icacos, knew what I was doing at my daily chores aboard White Puss. This cat boat, now twenty six years old, was showing her age. Most of my time was spent burning off old paint, sanding and painting. "Uncle Charlie" replaced some rotted planking. When conditions improved to the point that the young master might take her out for a sail, Cap Walsh just happened to be on hand. I'll never forget that first unsupervised venture out of the yacht basin. Although the weather was clear, the wind must have been at least fifteen knots out of the northeast. The tide was ebbing at a good three knots. White Puss under power would do only a little over four. My buddy, Hank Davis, who had never sailed before in his life, was my crew. Cap Walsh and "Uncle Charlie" were watching from the pilot house on the Icacos as I proudly pulled the flywheel through compression. The impulse magneto said clickum and the single cylinder engine chugged to life. We waved goodbye and soon were pitching somewhat awesomely in seas that fetched all the way across the river from Carney's Point. Undaunted I told Hank to pull up the throat halyard while I raised the peak, keeping one knee against the steering wheel. So far so good, but when I told Hank to push the button that killed the engine, things changed in a hurry. As we fell off on the port tack, the sail filled with a suddenness I had never imagined. The sheet was fouled around the reverse gear handle and we heeled way over nearly throwing Hank into the water. By the time I freed the sheet, White Puss had brought herself into the wind with much flapping of canvas and rattling of rigging. Hank looked at me with tea-cup size eyes and I lied to him that everything was perfectly alright. In a few seconds White Puss decided to run the experiment on the starboard tack. I responded by getting the sheet all fouled up in the steering wheel. Hank held on this time, but his facial expressions showed he did not like sailing, based on experlence to date. We continued in this mode for quite a number of cycles. Although I learned to manage the sheet and steering wheel, White Puss continued heel-over and head-up in total disregard for my strenuous efforts. I simply could not keep her off the wind long enough to get headway. I knew I was a good sailor, but this day things were sure different. Finally, to Hanks enormous relief, I declared that there was too much wind. We started the engine and furled the sail. With the engine at full throttle, we made a nice wake pushing against the current, but White Puss kept trying to veer sharply to one side or the other. Objects on the shore seemed to stay in the same position they had held when we were wrestling with the sail. We weren't going anywhere against that tide. Hank, looking out over the bow, remarked that he thought there had been an anchor up there on the deck. I looked, and behold, - no anchor - oh, there's a line overboard! Aha, it all came clear: That first puff in the sail neatly set our anchor. Everything we did afterwards was just exercise. When we got the anchor up, we returned to the yacht basin and heard Cap Walsh's verdict that the weather was too windy for sailing anyway. During 1937 I must have become somewhat more proficient as a small boat captain. At least my parents didn't interfere with a number of two week cruises around the upper Chesapeake Bay. But with old wooden boats one spends more time fixing than cruising. In all honesty I spent most of the summer at the wharf in New Castle. There I got to know some of the local kids who used the property as a swimming hole despite the best efforts of Mr. Camell. They mercilessly referred to him as Jelly Belly. That winter, schoolmates Angus Echols and Tom Ellis joined me in a syndicate. We bought a thirty eight foot Friendship Sloop, named Albatross, which was in winter storage at the Marine Construction Company. She was older and far more rotten than the White Puss. We had to work hard all spring for a June launching. We got her to the New Castle Yacht Basin, but there was much still to be done. It was sickening when Tom pulled off some sealing in the forepeak and demonstrated how he could remove the rotten frames with a corn broom. Despite the rigorous schedule required in getting the Albatross in shape, Tom and I found time to sail the White Puss to Norfolk, Virginia, where my sister gave her a new home. By August we thought the Albatross was ready for a cruise and we got as far down the Chesapeake as the mouth of the Chester River. We were sailing nicely on a pleasant southwind with a little sea running when I went to the galley to make some mid-morning coffee. I swung down the forward hatch into knee-deep water. We get the sails off and plied buckets and pump to discover an uncharted region of rot around the mast step. It took round-the-clock pumping for two days to motor back to New Castle. There, "Uncle Charlie's" electric pump was put aboard so we could sleep and figure out what to do next. The decisionwas made for us when someone "borrowed" the Albatross, put her ashore on Pea Patch Island and the wakes of the passing ships broke her into little pieces. After salvaging the hulk, I went away to College, the war came, the Icacos was given to the Navy, and I had no occasion to spend time at the yacht basin again. I fear these reminiscences are of little historic value, but I had fun putting them on paper. It was good to talk with you on the Cruise. Sincerely, IduPJ/rw Irenee du Pont, Jr.